Shanmuganathan Rajasekaran

Ganga Hospital is located in the city of Coimbatore, South India. This mid-sized city, by Indian standards, has a population of 3.5 million, and the hospital also caters to patients from a rural population of three million more. It lies in one of the most industrialized districts of Tamil Nadu and is noted for textile and manufacturing industries, educational institutions and specialty hospitals that provide affordable care.

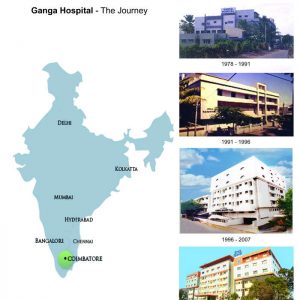

Ganga Hospital is a dedicated center for trauma, orthopaedics and plastic surgery. Since its inception in 1991, the hospital has steadily grown into one of the largest units in these specialities in the world. With 510 beds and 21 operating rooms, in 2016, it had 154,452 outpatient attendance and performed 25,462 surgeries. A current expansion program will increase the facility to 610 beds and 36 operating theaters dedicated to orthopaedics and reconstructive plastic surgery (Fig. 2-1). The Spine department alone registered 16,422 new patients and performed 3,412 spine surgeries in 2017. Clinical volumes apart, the hospital is also a reputed academic institution with resident and super specialty training fellowships and is well known for its research and high volume of publications.

I feel privileged to recount the 25-year history of the unit and trace the growth and development of a novel “Low cost - High quality” healthcare model that succeeded in taking the benefits of medical advances to the poor and needy.

ORIGIN AND GROWTH

Ganga Hospital was started in 1978 by my parents, Dr. J G Shanmuganthan and Mrs. Kanakavalli Shanmuganathan (Fig. 2-2). Being an anaesthetist, my father started a 17 bedded hospital where visiting surgeons could utilize the operating theaters and his anaesthetic services. My mother, despite her non-medical education, used her strong innate administrative skills in planning and successfully nurturing the growth of the hospital. My brother Dr. Raja Sabapathy, a plastic surgeon, and I returned to India after further training in our respective fields in UK and USA in late 1991 and started a specialty center for orthopaedics and plastic surgery.

Dr. S Rajasekaran, Orthopaedic and Spine Surgeon along with his brother Dr. S Raja Sabapathy, Plastic Surgeon.

While training to become medical graduates, we had the opportunity to read the book “The Doctors Mayo” that sparked our dream to establish a similar institution that focused on clinical excellence, academics and research. Some of the principles that we adopted helped us to develop the institution as per our dreams. First, we realized that it would be necessary to build and administer the institution ourselves and maintain it as a surgeon- and patient-oriented organization. Administration was kept as lean as possible with focus on helping the surgical team to achieve their clinical goals. This allowed us the luxury to practice medicine based on core values of medical professionalism and service rather than to be a part of larger corporate hospitals administrated by business heads.

Second, as we grew, instead of branching out and growing into a multi-specialty hospital (as most other growing institutions did), we remained focused on the twin specialties of orthopaedics and plastic surgery. Advanced radiology, neurosurgery, internal medicine, general surgery, intensivists and cardiologists were included to cater to the needs of the inpatients, but the core departments remained the same over 25 years. Staying focused on our interests and investing our entire human and financial resources into these two departments helped us to achieve international standards of care with excellent clinical outcomes. Third was our focus to invest maximally back to the hospital to maintain a steady progress and development. While we were frugal on luxury in our personal lives and hospital activities, we never faltered to invest for safety and progress.This helped us to improve outcomes that built our practice without any need for commercial advertisement or business promotion. Fourth, we built a team that was woven together by a passion for the profession rather than on monetary returns. We were very careful throughout to build the team from our trainees and fellows who shared the vision and who were enthusiastic to join the team. Chosen members were trained to excellence in their fields of interest rather than recruiting talent from outside. The team worked on fixed pay rather than reimbursements from case to case. This allowed the team to be focused on the medical needs rather than on the paying capacity of the patient.

THE FIRST DECADE

The initial success and reputation of the hospital was built on excellence in trauma care, but the present working model was developed and perfected in the first decade. Being a growing city and placed in an industrial district, the incidence of road and industrial accidents was high, often leading to amputations and permanent disability. We established new treatment protocols with introduction of advanced limb reconstruction and microvascular facilities that helped save many limbs and return people to occupation (Fig. 2-3). We made the standard of care uniform with consultant cover available twenty-four hours of the day and also made the cost very affordable. This built the reputation of the hospital and resulted in increased patient flow forcing quick expansions from 17 beds to 45 beds in 1995, 135 beds in 1998. The protocol of simultaneous reconstruction of bone and soft tissues led to development of “Ganga philosophy of care of open injuries” and the “Ganga Hospital Open Injury Severity Score,” which are well published and practised throughout the world. During the several expansions that we have had, we were particular to have 30% of beds for the poor who required subsidized treatment. Long bone fracture treatment either by interlocking nail or plate fixation could be possible for 400 USD and successful replant of amputated limbs for as low as 2000 USD. This made the hospital a household name and the preferred center for trauma care in the region. When patient numbers increased significantly, we made sure that the demand, not increase of treatment costs and revenue, led to expansion of services. Although we were the only unit to provide cutting edge services of replantation, advanced limb reconstruction and complex spine deformity, we did not follow the traditional business model of capitalizing on monopoly to increase cost to patients. We did the opposite to utilize the increased turnover to further reduce costs. The policy to keep the services affordable for all was strictly maintained.

The successful outcome of surgeries and restoration of mobility and life to patients steeply increased the patient flow and gradually led to the establishment of many sub-speciality departments, the first of which was the Spine Surgery unit.

SPINE SURGERY UNIT

The first spine surgery performed at Ganga Hospital was an open fenestration for disc herniation on October 20, 1991. In 1992, we acquired an operating microscope with a bank secured loan to perform microdiscectomy. The purchase of the first C-arm had to wait for two more years, as the finance returns and income was too low to convince any bank to provide the loan. The initial expansions were major financial challenges; each was overcome through a multitude of sources, including pledging of all personal belongings to the last cent and a tremendous amount of help from many friends and relatives. Micro spine surgeries, spinal fixations (including pedicle screws) and complex spine deformity correction surgeries were introduced to this part of the country. In the early 1990s, patients considered surgery on the spine as dangerous and a last resort. Over a period of time, consistent good outcomes and satisfied patients brought more patients to the unit. The draining area of patients seeking the hospital steadily increased to spread all over the country. By 1996, the orthopaedic department drew more than 150 outpatients every day. Nearly 70% were referred by satisfied patients, presenting themselves without appointments. It was very common for patients to bring their friends and relatives with orthopaedic needs during their follow-up appointments.

As our patient population increased, we had many unexpected challenges to surmount. First, our overseas training appeared inadequate to deal with the spectrum of local pathologies. Patients with severe trauma, infections and complex spinal deformities presented themselves at the end of the natural history of the disease and with many complications due to neglect (Fig. 2-4). The management of such problems was medically challenging. Second, many patients were illiterate, placed blind faith in us and often expected a miraculous cure. Families from rural areas of belived strongly in ‘treat my child as you would yours’ and would not entertain further discussions on treatment options and potential complications, which was also often over burdening. Third, 95% of patients had to pay for treatment as they were not insured, and unaffordability was often the cause of medical neglect. Children with gross deformities with or on the verge of complications were ushered by parents who had high expectations and meager financial ability, and they all had the same question, “How much will it cost to make my child normal again?” To place a price on the well being and health of such poor patients was mentally overwhelming. Clearly, there was a need for a new system where patients were not just medically treated, but were also supported economically and socially. Fourth, we needed to establish a service which was able to deliver safe surgeries for complex problems on a large scale. Patients who neglected primary treatment due to poverty cannot afford treatment of a complication. Nor could they withstand an extended absence from work due to complications as many worked on a model that delivered heath care of the standard of a developed nation at the affordability of a developing nation.

We were determined to overcome these challenges and inked this determination in our vision and mission statements in 1998 (Fig. 2-5).

In the development of a treatment model with high quality and low costs, we found inspiration from two South Indian medical institutions who performed extraordinary work. Aravind Eye Hospitals,1 a chain of eye hospitals across the country, in their mission of “eradication of preventable blindness” perform more than 300,000 free cataract surgeries (with outcomes comparable or better than western centers) every year for poor patients. Narayana Health,2 a multi speciality hospital in Bangalore that performed open heart surgeries for neonates at an astonishing low cost of 1000 USD with high success rates.

Their experience helped us innovate a model that allows us to perform about 24,000 and more orthopaedic surgeries every year (>3000 of them are spine surgeries), of which one third are done at highly subsidized costs. Uninstrumented lumbar decompressions could be performed for 175 USD, single level fusions for 600 USD and scoliosis correction for 1200 USD. This cost includes investigations, inpatient costs, surgical implant costs, drugs and disposables, professional charges and post-operative care. Although the low reimbursement nesessitates the surgical team to forego any surgical fees. A loss is incured in 20% of the patients treated, but the unit continues to treat more than 1000 patients every year under this program.

Ganga Philosophy of Care

I would like to discuss some of the principles we followed that led to the growth and success of the unit. It is our pride that over the years, these principles have been a guiding factor for many of our trainees and visitors who have established successful services in their hometowns benefitting many more thousands of patients.

1. Fulfill an unmet need in society and make it affordable

Providing a service, which fulfills a hitherto unmet need in the society, and keeping it affordable fosters rapid growth. In the early 90’s, 24/7 consultant cover for trauma care with skills in microsurgery, advanced limb reconstruction and safe anaesthesia were not available in the city. Providing these services to a population of more than 6 million with high incidence of road and industrial accidents established a setting for success. When the volume increased, the team strength was strategically and continuously increased to meet the needs. Having skill sets which were not available in the region allowed us to literally monopolize limb salvage surgery and advanced spine surgery in the region. Rather than use the demand to increase the revenue, we utilized the increased turnover to spread our running costs thin and reduce treatment costs. We have been particular to remain inclusive and be affordable to all sections of society. Being affordable builds up volume and volume builds up experience of the team and operational efficiency, which in turn can help to keep the cost down.

The successful model of collaboration in trauma was extended to other areas of need in society by both the orthopaedic and plastic surgery departments which led to many niche super-specialty units such as spinal deformity correction, hand injury service, limb revascularization facility, brachial plexus surgery unit, post burns deformity reconstruction, Spine injury rehabilitation unit etc.

2. Be frugal on luxury and lavish on safety

In a self-pay society expectations from patients are higher than in a society where the government provides services. To gain society’s trust, one needs to provide safe and good outcomes. We made these our only interests in all our decision-making, and we continually invested in high end equipment and cutting edge technology. Government subsidies for medical institutions are non-existent in India, and one is forced to work with bank loans with steep interest rates of 10-15%. Our initial growth period was a struggle, and it took more than three years to accumulate funds for purchasing the first C-arm. However, the policy of investing back heavily on equipment has now ensured that the 18 operating theaters and diagnostic departments at Ganga Hospital are state of the art. Visiting surgeons from developed countries are often surprised to find the operating rooms equipped with advanced equipment like intraoperative AIRO CT guided navigation, Iso-C 3D C-arms, high end operating microscopes and dedicated C-arms for every operating room. Treatment of complications are costly and avoiding this expenditure helps to have a positive balance for improvement.

While we are liberal in investment for accuracy and safety, extreme frugality is followed wherever resources could be saved. Utmost thriftiness is followed in avoiding investments on comforts, duplication of services and unnecessary use of disposables. There is also a focus on conservation of resources by streamlining of procedures and improving efficiency of work, turn around times and downtime in operating rooms. The saved resources help to fund high end technology for safety of the patient.

In 2017, the launch of the “Ganga Air Ambulance” as the first ever hospital-based ambulance service in the country was not only a moment of pride but was also a practical testimony to how an efficient and sound administration can make even major medical advances practically possible (Fig. 2-6).

3. Maintaining a high performance work culture

The cost of any service can be high or low depending on the efficiency of the team. Providing subsidized treatment can be facilitated by a culture of hard work and high performance of the entire team. They have to be passionate about the cause and consciously work towards making cost subsidy for patients a possibility. Visitors to our department are always impressed with the work culture that allows our operating theaters to start early at 6:30am and often finish as late as 7:00 or 8:00pm everyday. The average turn over time between surgeries is on an average less than 20 minutes which allows us to perform five to six major cases everyday in each operating room allowing nearly 100 major surgeries to be performed each day. This is significantly more than the average in many hospitals. This saved operating time is used for subsidized surgeries. Only an environment that promotes efficiency and high performance can deliver low-cost, high-quality health care. This is not possible in a work-to-rule environment with a low performance attitude.

4. Surgeon managed unit with low profile administration

World over, the medical fraternity is struggling with effects of domination of administration over surgeons. When health care decisions are driven by business administrators, cost subsidy is not prioritized. We have been fortunate remain in command of the critical decisions that gave us the flexibility to set surgery costs at variable levels based on need and affordability of patients. When complications occurred, we could waive costs without getting the approval of an administrator. It allowed us to use high technology such as intraoperative CT navigation or spinal cord monitoring for free surgeries, extending safety and good outcomes to all. Although medical equipment has a high initial investment, running cost per patient is often very low. Not utilizing such equipment for poor patients at free or subsidised rate to enhance safety did not make clinical sense. We have been very fortunate to have the entire team led by our consultant surgeons who have willingly participated in the administration and smooth running of the unit (Fig. 2-7).

5. Power of focused family

To this date, against all odds and in spite of tempting business offers, we have remained a family managed unit and resisted the attractive offers of venture capitalists and corporate expansion to a public limited company. The hospital growth and success has been an example of the collective force of a focused family. Although from a non-medical background, my mother, my brother’s and my wife share our interest and are involved heavily in various administrative aspects of the different departments (Fig. 2-8). This has helped the men in the family to concentrate on professional work and advancement of the institution. This has maintained the character of our unit, that the policies are surgeon managed and driven with little administrative dominance. I should mention here the involvement and willing participation of all senior consultants in various aspects of daily work and administration that has helped the smooth function of the unit. It is fortunate that all of them have integrated into one large “Ganga family.”

6. Overcoming the challenge of avoiding two standards in treatment

The principle of avoiding two standards of treatment to the normal paying and subsidized patient enhanced the reputation of the institution. Apart from the factor that local implants were preferentially used for charity patients, there was no difference in the surgical team, techniques used, technology utilized and postoperative care. This was made possible by the unit’s philosophy of allocating surgical expertise and technology as per needs of the patient and not on paying ability. The knowledge of who was a paying and who was a subsidized patient was often closed-door information limited to the senior surgical staff to avoid any discrimination and bias by the treatment staff. All surgical staff worked on fixed pay basis. This helped focus on the medical needs of the patient without any bearing on his paying potential. This ensured the same service and equal care amongst all patients.

While safety is an important aspect of any surgical program, it is the lifeline of a subsidized service. Complications are expensive and a waste of time and resources that could have been used for other deserving patients. Longer hospital stays spell disaster for families that live on a “no work, no pay, no food” condition. Lack of disability insurance and government support for treatment means poverty and starvation for the remaining family. Complications also reduce the morale of the staff and deter organizations that may fund these charity initiatives.

7. Charity woven into daily work

We routinely integrated social commitment and charity into our everyday work. Most talented surgeons work in a health care model that does not allow charity work. They then allocate only a certain period of days for charity at a place far away from their normal work. This could lead to reduced quantum of service and also two standards of care as often place designated for charity work have poor facilities. We decided that charity should be a part of our everyday work and should be performed in the same place as our everyday work. Rather than the team travelling to different places, we encouraged patients to come to the hospital. This model was more effective, time saving to the surgical team, cost effective and safer to patients. Patients availed the same high standard of treatment by the same team with good results. By integrating poor patients into the large patient pool that could afford treatment, we were able to cross subsidize treatment for them easily.

8. Partnering with society for free surgeries

Many wealthy patients and service organizations are keen on helping needy patients through projects that use their funds honestly. This helped us set up a series of projects, which engaged the society and service organizations, including the Rotary Clubs in our city.

The first initiative “Project Helpline - Help for the Helpless” was launched in 1998 with an aim to provide free corrective surgeries for poor children with deformities of any aetiology.We perfected a model where patients chosen to be funded by the project could be treated at 10-20% of usual cost. Unlike service organizations that often used a significant percentage of the donation for administrative costs, we used 100% of the donated funds towards treatment costs. This project has been successfully running for the last 16 years benefitting thousands of poor children.

The success of this project helped us launch many more social service initiatives such as “Save the working hand,” which provided free or subsidized surgeries for industry related accidents of poor patients; “Hope after Fire,” a project for free corrective surgeries post burn contractures; and “Project Swasam”(a breath of new life), a project for subsidized treatment of adult deformities. It is noteworthy that thousands of patients have benefitted from these projects and the value of the subsidy in treatment would run into millions of dollars.

9. Project Happy Spines – Complex deformity correction for USD 1200

The correction of complex spinal deformities at low cost was perhaps the most challenging. In 1994, the state government also introduced a “Below-poverty line” scheme where poor people could avail themselves of surgical treatment in private hospitals with a maximum reimbursement of 1200 USD per patient for any surgery. This led to a number of patients from all over the state seeking corrective surgery who had neglected their spinal deformities for want of funds. While almost every hospital restricted their services under the scheme to simple surgeries, we decided that it was morally inappropriate to adopt the policy of “Pick and Choose” in patient pathology. Project Happy Spines was a culmination of all our experience gained on patient subsidy. The availability of a subsidized ward was particularly useful for patients living far away and requiring staged surgeries.

We analyzed the treatment costs with view to subsidize treatment. On an average, 30% of the cost of treatment was towards professional fees, 30 - 40% of cost was towards implant, equipment and drugs costs, and the remaining was towards hospital stay charges. The following strategy helped us to reduce costs for the poor and needy patients by almost 90%. Surgeons and anesthetists provided their service free, and this reduced treatment costs by 30%. We realized that substantial reduction in implant costs could be achieved by manufacturing them locally. We benefitted from the experience of Aravind hospital on this front. In the quest for overcoming preventable blindness, Aravind Hospital realized the high costs of imported implants was the road block in providing free cataract surgeries. They manufactured high quality lens and suture materials that were one twentieth the cost of imported lens. This allowed them to exponentially increase the number of free surgeries they performed. Inspired by Aravind, we collaborated and encouraged indigenous implant makers (without any financial relationships or benefits) to produce pedicle screws of acceptable quality for 40 USD. By early 2000, we had reliable, well-designed implants at one-eighth the price of imported screws, reducing implant costs by about 80%. We also frequently used low implant density constructs and sublaminar wires which kept implant costs for deformity correction to below 400 USD (Fig. 2-9). For the few patients requiring imported implants, we convinced multinational implant makers to adopt our project as their Corporate Social Responsibility undertaking and provide free or subsidised implants. Pharmaceutical companies enthused at our initiative, actively participated with free samples of antibiotics and essential medicines that brought down the costs still further. Overall, we were able to perform 30% of our spine surgeries at 20% of the usual costs. To this date, the number of such subsidized or free surgeries performed exceed 10,000. In recognition of this service to the society and for carrying the benefits of modern spine surgery to the needy in society, we were awarded the prestigious Walter Blound Humanitarian Award by the Scoliosis Research Society in the year 2015 (Fig. 2-10).

Academic Development

The next few years saw the transformation into an academic unit. Daily morning clinical discussions were started in a makeshift structure at the roof top in 1994. A formal academic program to include journal clubs, seminars, clinical-radiology seminars, multidisciplinary rounds of Polytrauma patients etc were designed gradually. Regular audits and mortality and morbidity meetings were also started leading to clinical and academic improvements. The unit was recognized and approved for resident training in Orthopaedics by the National Board of Examinations in 1996 and subsequently for several other courses both by the NBE and our state MGR medical university. Currently the hospital remains one of the largest providers of formally recognized residencies and fellowships outside the Medical school institutions (Table 2-1). Entry into these fellowships is highly competitive and through national entrance tests and have a tough exit exam. We are proud that we have provided higher training for more than 282 doctors for our country and 212 overseas doctors through these fellowships.

Research and ISSLS

World over, research is often performed due to professional compulsions or due to a passion to find solutions for clinical problems in everyday practice. We have no professional or institutional compulsion for research. My membership to ISSLS opened the doors for life-long journey to meaningful clinical research in low back pain. I was fortunate to be selected as the International fellow for the ISSLS meeting in 1996 at Marseilles, France, and the exposure made me realize that there was more to spine surgery than just surgery alone. It was a transformational experience. The fellowship was instrumental in converting our unit from just a clinical to clinical-research unit, and I am grateful to ISSLS for the same.

As in clinical work, we are proud to have evolved a simple, economical and effective research model that has been successful in producing many internationally recognized awards and publications. From the beginning, the two main challenges we faced were paucity of quality time for research and securing funds for research. Most of the medical staff worked 14 hours a day, and research at the end of a busy and tiring day was a challenge. Without compromising clinical work, research time had to be managed at the at the end of the day’s work or by sacrificing weekends. A greater challenge was to secure funds and grants. In developing countries, research funds are focused on areas like maternal and infant mortality, preventing malnutrition, overcoming blindness, etc., and there is low priority for non-communicable diseases like low back pain. After many unsuccessful attempts, we decided that the way to proceed was to create funds internally and find ways to do low cost research. We allocated a certain amount of departmental funds for research to meet the basic costs. Costs were kept very low by all staff performing research for free and utilizing hospital facilities like MRI services out of office hours. Our first ISSLS prize winner in 2004 required multiple MRI images in 81 patients. We counseled our patients and got them sufficiently interested to have their MRI imaging late in evenings or early morning when the MRI machine was idle. The MRI scans were obtained for a cost equivalent of 30 USD each. Other expenses like the use of contrast Gadiodamide were funded though personal means. I am confident that our ISSLS award in 2004 was perhaps the lowest funded ISSLS award project, as it cost us only about 16,000 USD (a significant amount for an Indian surgeon but miniscule by international standards).

The Ganga Orthopaedic Research and Education Foundation was set up in 2000 with a personal donation. We improved this fund over the years by investing the profits from our educational courses and also the prize money from our various awards. Although we were starved for funds, it is to our credit that all the funds were internally generated, and to date we have strictly avoided participating in any clinical trials involving drugs or devices on any of our patients. We felt it morally wrong to subject any of our patients to unproven technology, be it either a drug or an implant. Industry support was restricted for educational events, and our research funding has been completely internal.The “high quality, low cost, clinically relevant” research model has worked very well for us, and the team has been the proud recipient of many prestigious awards (Table 2-2).

The research team was very lean but ready to multitask. Every member of the team had an input in writing proposals, performing and overseeing the project, collecting and analyzing data and also writing the paper. Lack of secretarial and other infrastructural facilities were overcome by personal involvement that made successful completion of the projects possible. Wherever there was a deficit in facility, we overcame it with a surplus in enthusiasm and innovations in research process.

Although to win an ISSLS award sometime during our career was a dream, we did not hope to be successful in our first attempt. The ISSLS award in 2004 boosted our confidence and reinforced the principle that meaningful and highly relevant research is possible in developing countries also. Asking the right question and choosing a simple and economical research method can overcome the need for large research labs and huge research grants. Enthusiasm and commitment of the team can overcome shortage of infrastructure and staff.

Contrary to the prevalent opinion that research in the setting of busy clinical work is impossible, our research work actually enhanced our interest in clinical work and prevented professional fatigue. Personally, our research projects in low back pain and disc degeneration made every single patient unique and interesting and helped to overcome monotony of a busy back pain clinic. Research also brought a closeness and comradeship within the research team. I am happy that this “Lean Research” process has guided many of our spine fellows who have subsequently won many awards in their own right.

Enthused by our success in clinical research, we established a basic science wing – the “Ganga Research Centre” – in 2014 for proteomics and genetic analysis of disc degeneration. Two full time basic science experts one with expertise in proteomics and microbiology and the other in biotechnology were inducted into our research team. We also entered into strategic collaborations with reputed research groups such as the Genetic Study department of TNAU, the research division of Aravind hospital and the University of Hong Kong. This helped us to surge ahead in the fields of genetic and proteomic research. It is noteworthy that the maiden work from the Ganga Research Centre on “Is infection the initiator of Disc Degeneration” was awarded the ISSLS prize, 2017.

Realizing the large gap in the need and availability for higher subspecialty training, we also instituted many informal fellowships, which are highly popular. The spine microsurgery courses and the micro-vascular anastomosis course conducted by the plastic surgery department are sought after by surgeons the world over. We have had 1269 doctors from 49 countries as visiting fellows to both departments.

QUO VADIS – FROM HERE TO WHERE?

Just like individuals, institutions also evolve over a period of time. We believe that every institution must reinvent itself every few years and continuously evolve into something better. This is crucial to maintain the enthusiasm of the team and its relevance to society. The first 25 years have witnessed tremendous growth. The first seven years was focused on unit building and consolidation. From 17 beds and two operating rooms, the unit has grown to 480 beds with 21 operating rooms. In 2016, 25,462 surgeries were performed, 80 to 90 major surgeries everyday. Surgeries rarely performed in other hospitals are routinely performed in large numbers daily. The unit is recognized by the society as the preferred center for treatment, and this has fuelled continuous growth. We have remained true to our mission statement of keeping our expertise affordable and available to all sections of society. The hospital has attracted and trained more than 2000 national and international doctors in the fields of orthopaedics, reconstructive surgery and anesthesia. We have the satisfaction of contributing relevantly to literature with nearly 400 peer-reviewed papers in high impact journals and many international and national research awards.

The question is the future. We are acutely aware that the next 25 years is more important than the past 25 years and certain guiding principles will be followed. We will remain concentrated and focused to the twin specialties of orthopaedic and plastic surgery to achieve excellence. We will maintain our character of being a surgeon driven unit without giving in to a corporate business culture. Growth will be measured not just in numbers but in overall progress in all four aspects that have defined our institution – clinical excellence, academics, research and giving back to society.The challenge will be to expand the “Ganga family” and build a team that will hold high the founding principles of the unit.

We have been socially relevant and the aim will be to be increasingly so. Spine surgery is a different specialty in different parts of the world as the pathology, disease presentation, affordability, expectations of the patient and health care providers are all different in each region. The right solution for a clinical condition in the developed world may not be appropriate in other regions. Our aim will be to innovate clinical solutions and health care models so that “appropriate medicine” to our society is evolved. These solutions must be delivered at an affordable cost to the society. Our success has ridden on the shoulders of a united and empowered team, and the spirit and enthusiasm has to be expanded to a larger team. Apart from sterling clinical work, the challenge of the seniors in the team will be to transfer the culture and spirit by being great coaches and mentors to juniors across specialties and departments.

The ultimate success will be to be steadfast on our vision and mission statements of being an institution of pride to our country and to make available our expertise to all sectors of society. In God we trust and with His blessings we will continue to move on.

REFERENCES

- Grovel Trust. Aravind Eye Care System. 2015. Available at www.aravind.org. Accessed on February 21, 2019.

- Narayana Hrudayalaya Ltd. Narayana Health. Bengaluru, India. Available at www.narayanahealth.org. Accessed on February 21, 2019.